The 67th CGPA: A peace

visionary and a transformative leader

By

OACPA

August 4, 2025

FORT BONIFACIO, Taguig City – Lt. Gen. Antonio G. Nafarrete assumed

command of the Philippine Army as its 67th Commanding General on

July 31, 2025. Upon taking helm of the Philippine Army, the 67th

CGPA has issued a guidance that focuses on holistic development of

Army personnel, the organization's most valuable resource. The

command guidance also puts premium on sustained modernization,

doctrinal refinement and organizational development anchored on the

convergence of institutional efforts and the enduring values of

honor, professionalism and duty.

Lt. Gen. Nafarrete is a full-blooded scout ranger who has been

deployed all over the country and seen combat action up north in

Kalinga and Apayao; in the Visayas in Negros; and down south in

Basilan, Maguindanao, North Cotabato and the Zamboanga Peninsula.

His career began as a platoon leader in the 10th Infantry Battalion,

1st Infantry Division (1ID) and progressed through various elite

positions, including being a pioneer in organizing the 1st Scout

Ranger Company when the First Scout Ranger Regiment (FSRR) was

reactivated in 1991. His key leadership roles included commanding

the 1st Scout Ranger Battalion from 2008 to 2010, serving in the

Presidential Security Group (now Presidential Security Command)

where he led protective details domestically and internationally

from 2011 to 2015 and later in commanding the Sulu-based 1101st

Infantry Brigade, 11th Infantry Division. He also commanded the

Army's 1st Infantry and 6th Infantry Divisions prior to serving as

the 19th commander of the AFP Western Mindanao Command in November

2024.

The 67th CGPA has a notable background in peace-building efforts as

he served as the Chairman of the Government of the Philippines’

Coordinating Committee on the Cessation of Hostilities, one of the

mechanisms under the Bangsamoro peace process with the Moro Islamic

Liberation Front, which forged an amity accord with the government

in 2014.

Lt. Gen. Nafarrete is a decorated leader who received numerous

military awards for his exemplary service. He received the Gawad sa

Kaunlaran Medal in 2022 during his stint as the 1ID Commander in

recognition of his contributions to the mission of the organization

achieving peace in the region. He also received three Gold Cross

Medals from 1998 to 1999 for his gallantry and combat achievements,

as well as the Distinguished Service Star in 2013 for his

meritorious Service. Even earlier in his career, he received the US

Parachutist Badge and US Ranger Tab from the US Army Ranger and US

Army Infantry School in Continental United States while also

equipped with the Scout Ranger and Paratrooper Badge from FSRR.

The 67th Army Chief also excelled in his military and civilian

schooling. He is a proud member of the Philippine Military Academy

“Bigkis-Lahi” Class of 1990. After graduating from the prestigious

academy, he continued his pursuit of academic excellence and

professional development. He underwent the Basic Airborne Course and

Scout Ranger Course early in his military career. He also took the

US Army Ranger Course at the US Army Infantry School in 1995 and

courses on Joint Transition and Joint Professional Military

Education at the National Defense University, USA in 2005. In his

pursuit of personal development, Lt. Gen. Nafarrete also graduated

with Masters in Management Major in Public Administration from the

Philippine Christian University on 2013.

In his first command conference, the 67th CGPA gave his marching

order for the 110,000-strong Philippine Army to stand steadfast in

its mission to provide responsible, credible and capable forces to

the AFP Unified Commands in support of the AFP’s Campaign Plan

“Tatag Kapuluan.”

Eight years since

Marawi conflict, unresolved issues of displaced and missing people

hamper lasting peace

|

The

most affected area in Marawi remains largely a ghost town

with over 8,000 of its former residents still living in

transitional shelters. (Photo by B. Sultan/ICRC) |

By

ICRC

May 23, 2025

MANILA – The path

to lasting peace remains fragile in Marawi City in southern

Philippines because of unresolved issues like prolonged

displacement, limited support and lack of answers for families whose

loved ones are still missing, eight years since the conflict.

“It is disheartening to

see so many families – around 8,200 people – living for eight years

in inadequate conditions in shelters that were supposed to be

temporary. They are now paying rent and yet have irregular access to

clean water, adding immense strain to their daily lives,” said

Johannes Bruwer, head of the Manila delegation of the International

Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

Although the Philippine

government has made significant efforts, such as the construction of

public infrastructure in the most affected area (MAA) and the

creation of the Marawi Compensation Board, rebuilding their homes

remains a distant dream for some families who claim that the

compensation they received is not enough and for those who are

burdened by the documentation required to receive their payouts.

The ICRC continues to urge

the national, regional and local governments – especially its newly

elected officials – to work together to hasten the rebuilding of the

most affected area while ensuring that basic services are provided

to people in transitional shelters.

“Eight years is a long

time; people have been displaced for far too long. For the

residents, returning to their neighbourhoods is a step toward

normalcy and a necessary part of their healing. Ensuring their full

recovery is not only a humanitarian imperative but also key to

lasting peace,” Bruwer said.

The ICRC has been helping

the people of Marawi access clean water, especially in certain parts

of the least affected area where water is now available

round-the-clock. The ICRC is looking forward for government agencies

to complete the remaining pipelines in Marawi’s water supply

network.

|

Eight

years on, displaced families in the Sagonsongan transitional

shelter still face problems with accessing clean running

water. (Photo by B. Sultan/ICRC) |

Over 300 registered cases

of missing people remain open

Since 2017, the ICRC has

advocated for people whose lives were upended by the Marawi

conflict, including the families of the missing. They continue to

suffer from the anguish and uncertainty of not knowing the fate and

whereabouts of their loved ones.

The obligation to prevent

people from going missing and to account for those who are reported

missing is enshrined in the Geneva Conventions and its Additional

Protocols, to which the Philippines is a party.

Apart from the emotional

burden, the difficulty of obtaining a legal document certifying the

absence or presumed death of the missing person has been repeatedly

raised as a major concern by their families. If this persistent,

systemic issue affecting all missing people is resolved by the

government, their families will be able to access social benefits,

pensions and property rights.

From 2017 to 2024, the

ICRC has helped more than 400 families of missing people by

providing mental health and psychosocial support and through

livelihood initiatives. The ICRC has been supporting the Philippine

National Police-Forensic Group with technical advice,

capacity-building and material support toward the identification of

remains in the Maqbara and Dalipuga cemeteries.

“We urge the Philippine

authorities to provide answers as soon as possible to the families

who have been patiently waiting. The authorities need to take the

necessary steps to clarify the fate and whereabouts of the missing,

as well as identify the remains that have been found. By doing so,

the government will help the families move toward healing and

trust-building,” Bruwer said.

He added, “Beyond just

remembering the missing people of Marawi, let us realize their

families’ shared hope for more support and for closure, so that they

can move forward with peace in their hearts.”

Crafting dreams

together

Susana

Grabillo and her husband proudly displayed their

handcrafted bags in their newly constructed concrete

home, reflecting their success in every life's

challenges. |

By

JOSEPHINE RAMOS

July 19, 2024

SAN PABLO CITY –

Susana Grabillo, 55, from Barangay Basiao, Basey, Samar, continues

to weave her dreams into a thriving venture with her husband on her

side.

Susana started helping her

parents at an early age. She initially weaved mats alongside her

mother in Saob Cave, while her father worked as a fisherman. Her

exposure to weaving from a young age enabled her to develop skills

in the craft.

As a child, she was always

eager to assist her parents. She began selling various fruits in

their barangay, which helped her buy school supplies.

In 1979, Susana's family

relocated to Manila where they made a living selling eggs. Despite

the challenges, she completed her elementary and high school

education. In 1994, she took a six-month vocational sewing course in

a facility in Pasay.

“I persevered in learning

sewing because I have bigger dreams for myself and my family. I know

I can do more," she said.

Susana got a job at a

sewing factory in Taguig soon after receiving her certificate, then

to Sucat after six months. She eventually settled in Makati, where

she spent many years sewing dresses for dolls. During this time, she

met her now husband, who had been a tricycle driver in Manila.

The couple decided to get

married in 1996 and settled in Pasay to start their own family. They

lived there for years before moving back to Samar in 2001. They

resided with her in-laws until they could build their own house.

"My brother-in-law loaned

us P1,500, which we used as capital to raise native pigs in 2006. We

began with a sow and sold the piglets. For two years, this provided

for our family's needs," Susana said.

Due to the challenges of

pig farming, Susana transitioned to cooking and selling pancakes and

ice candy in a school close to their home while her husband worked

as a helper in a handicrafts factory. Her husband gradually learned

the weaving himself just by observing.

They got inspired to start

a handicraft business as it was easy for Susana to learn weaving

with her skills in sewing. In 2012, with just P700.00, they began

crafting slippers and coin purses from tikog grass. Over time, their

product line grew to woven bags, baskets, and mats.

"My husband became my

business partner. He would sketch product ideas, and I would figure

out how to bring them to life. This is how we expanded our weaving

skills and knowledge," Susana said.

Their business was

thriving until typhoon Yolanda struck in 2013. All their products

and weaving materials were destroyed, including their home. During

this time they received support from NGOs and CARD Bank, a

microfinance-oriented rural bank they had been a client since 2011.

"Even before Yolanda

struck, CARD Bank supported my business. I frequently applied for

loans to add to our capital. After Yolanda, I again utilized my

loans to purchase materials and restart," she said.

They slowly regained their

strength to start again, setting up a small hut to display a few

handicrafts they made. Fortunately, they found buyers from Manila,

Davao, and Cebu. They also seized the opportunity to bring their

handicrafts to Manila and participate in trade fairs, further

expanding their customer base.

The pandemic in 2020 posed

no hindrance to them as orders continued to flow. With her husband

by her side, they continued weaving in their small hut until they

were able to rebuild a concrete house in 2022.

"We are immensely thankful

to CARD Bank because, without the loans they provided, we wouldn't

have been able to sustain our handicraft business. They also opened

up greater opportunities for us; now we are suppliers to Mga Likha

Ni Inay," Susana expressed gratefully. MLNI is a member institution

of CARD MRI that aims to support microfinance clients in marketing

locally made products.

Susana's coin purses and

laptop bags are now available at the Mga Likha Ni Inay store,

providing a new way to introduce their product to more customers.

Currently, Susana has an

existing loan of P50,000 at CARD Bank, Inc., and plans to apply for

a bigger loan in the future to further expand her business.

For Susana, maintaining

hope and resilience during uncertain times is crucial. Despite

facing numerous challenges in life, she persevered with her dream,

and her determination has been rewarded with a thriving venture.

From roots to triumphs

|

Virginia

A. Orollo, an entrepreneur and CARD client from Leyte, has

proven that anyone can turn a business from humble

beginnings into entrepreneurial success. |

By

EDRIAN BANANIA

July 15, 2024

SAN PABLO CITY –

Virginia A. Orollo, a 50-year-old mother of 13 from Lourdes,

Pastrana, Leyte, shows how hard work and dedication can turn dreams

into reality. Her life is a true example of perseverance and

determination.

Growing up in a simple

family, Virginia learned the importance of hard work early on. Her

family's primary source of income came from selling local

vegetables, root crops like cassava, and homemade Filipino

delicacies. These humble beginnings taught her the values of

perseverance and dedication, which she carried into her own family

life and business ventures.

Virginia inherited the

skills to make binagol, a popular delicacy from Leyte made from root

crops like cassava and taro. Since the 1980s, she has mastered this

craft, which has become her main way of supporting her family.

"Making binagol requires

patience, effort, and time, just like achieving our dreams,"

Virginia shared.

Virginia and her family

faced numerous challenges, including a lack of raw materials,

shortages in business capital, difficulties in product distribution,

and building a business trademark in the community. Despite these

obstacles, she overcame them all with confidence and perseverance.

As the business grew, so

did the capital needs. In 2016, she met CARD, Inc., (A Microfinance

NGO), and took out her first small loan of P3,000, which later

increased to P15,000. She invested this money in her business.

"My journey as an

entrepreneur has been like a roller coaster. Many ups and downs

tested my patience and determination. But, with the support of my

family and help from CARD, I kept going and never gave up," Virginia

reflected.

During the COVID-19

pandemic, Virginia, her husband, and her two children continued

producing binagol, ensuring a steady income despite the crisis. "No

matter how many storms like Yolanda and pandemics come into our

lives, we will remain resilient and faithful to God," she said.

Their determination and

patience paid off. Their product, now officially named "Virginia",

is registered and approved by the Department of Trade and Industry.

From struggling to find

suppliers, Virginia now has loyal suppliers of raw materials, and

her binagol is showcased in one of the pasalubong centers in

Carigara, Leyte, significantly increasing their customer reach.

The price of Virginia

Binagol is P50.00 per piece and is delivered in bulk to customers

three to four times a week.

"To those who want to

start a business, it's crucial to focus on maintaining the quality

of your products and services. This is how you stay present in the

business world," Virginia concluded.

Looking to the future,

Virginia hopes to pass her skills on to her grandchildren and future

generations. She believes that instilling these values and skills in

the younger generation will keep their family legacy alive and

empower them to face life's challenges with patience and

determination.

Virginia's journey shows

the importance of perseverance, dedication, and the unwavering

support of family and community in achieving one's dreams. Her

success story of turning root crop products into a thriving business

will inspire others to pursue their passions and positively impact

their lives.

Challenges and

opportunities in embracing Distance Learning: Insights from NMP

study

|

Ms.

Zenaida Eugenia D. Palita, presenting the research findings

on Investments on Distance Learning in Philippine Maritime

Training Institutions during the DMW-NMP Maritime Research

Forum on June 20, 2024 at Hotel H2O, Manila. |

Press Release

June 27, 2024

TACLOBAN CITY – In

response to the accelerating digital transformation within the

maritime industry, the National Maritime Polytechnic (NMP) conducted

a research study on the Investments on Distance Learning in

Philippine Maritime Training Institutions (MTIs) in CY 2023.

Findings of the study

unveiled that among the 87 surveyed Maritime Industry Authority

(MARINA)- accredited MTIs, 49% (43 MTIs) have incorporated distance

learning into their programs, with 39 providing responses. These

institutions made substantial investments in manpower, technology,

and infrastructure to comply with MARINA Advisory No. 2020-59. This

included hiring trainers, IT staff, and administrative support, as

well as upgrading of information and communications technology (ICT)

infrastructure like Learning Management Systems (LMS), internet

connectivity, and training facilities.

Manpower resources were a

crucial focus, with varying compensation schemes and a need for

additional training among instructors and assessors to effectively

deliver online training. Most MTIs relied on existing staff or

trainers to transition training materials to online formats, with

limited involvement of external subject matter experts (SMEs). MTIs

primarily utilized cloud-based LMS like Google Classroom and Zoom,

though stability of internet connectivity remained a concern,

addressed predominantly by increasing bandwidth rather than

acquiring new connections.

Financial constraints

emerged as a major barrier, alongside preferences among instructors

for traditional face-to-face teaching methods and the challenge of

meeting MARINA's stringent compliance requirements for online

training accreditation.

These concerns were echoed

by MTIs that have yet to adopt distance learning, who also cited

inadequate internet infrastructure as a significant obstacle.

Post-pandemic, some MTIs

reported reduced demand for distance learning, attributing it to

improved health conditions and the preference for in-person

training.

These findings underscore

the need for targeted support and streamlined regulations to

facilitate broader adoption of distance learning among Philippine

MTIs, ensuring they can effectively integrate digital solutions into

maritime education and training to meet evolving industry demands.

The study recommends

significant actions for the Philippine government, including

upgrading of ICT infrastructure and providing high-volume,

high-speed internet access, particularly in underserved areas and

public institutions. Legislative measures are urged to ensure

reliable internet and power supply across the country, crucial for

seamless online education. Furthermore, partnerships and agreements

with telecom companies are encouraged to provide stable connectivity

and support IT infrastructure development.

Government subsidies,

funds, and scholarships are proposed to support MTI personnel and

seafarers participating in distance learning, alongside policy

support, research, and regular evaluation of online education

initiatives. Public awareness campaigns are also recommended to

promote the benefits of distance learning in maritime education.

It was also recommended to

MARINA to simplify accreditation processes with clear guidelines and

standardized training standards applicable to all MTIs in terms of

STCW mandatory training courses. Flexibility in regulatory

frameworks is advised to expedite the adoption of distance learning

methods. The establishment of specialized training centers and the

standardization of software used in distance learning are emphasized

to ensure consistency and quality across institutions.

The study advocates for

further research into the advantages and challenges of online

training within Philippine maritime education, aiming to

continuously refine educational practices. These recommendations aim

to create an enabling environment for advancing distance learning in

Philippine MTIs, aligning education with industry demands and global

trends.

World Water Day:

Bringing safe drinking water closer to conflict-affected families in

Misamis Oriental

|

Ishfaq

Muhammad Khan (third from right), head of ICRC’s Butuan

office, joined residents, officials from the local

government unit and PRC volunteers during the handover of

Alagatan’s new water system. (Photo by M. Lucero /ICRC) |

By

ICRC

March 20, 2024

MAKATI CITY – For

years, the people of Barangay Alagatan in Gingoog City, Misamis

Oriental, have had a difficult time getting clean drinking water.

Their situation worsened in 2022, when an armed conflict prevented

them from going to the nearest spring, their only source of safe

water. However, a newly completed water supply system, one that the

residents have built themselves, is set to improve their standard of

living.

The new water supply

system, built by the villagers through a cash-for-work program, was

a project implemented by the International Committee of the Red

Cross (ICRC) in coordination with the local government. It was

unveiled on 7 March 2024 during a handover ceremony attended by

community members, local authorities and representatives of the ICRC

and its partner, the Philippine Red Cross (PRC).

ICRC engineers designed the system, supplied the materials and

equipment, and provided technical support to the construction works.

Approximately 700 people will benefit from the project, and the

system provides water to the barangay office, elementary school, and

health centre.

The completion of the

water system comes just around World Water Day on 24 March 2024.

Commemorated annually, World Water Day aims to raise awareness about

the billions of people around the world who do not have access to

clean and safe water.

“People in remote areas

are at a higher risk of getting life-threatening diseases if they do

not have access to clean water. Having a reliable water system

improves a community’s hygiene standards, and it also helps them

sustain their livelihoods. This project, completed just a few weeks

before World Water Day, is a step toward the improvement of living

conditions in Alagatan,” said Ishfaq Muhammad Khan, head of the

ICRC’s Butuan office.

Almost 85 residents

started constructing the water system in September 2023. They

installed a five-kilometer pipeline, five storage tanks and 19 water

faucets.

On 5 March 2024, a hygiene

promotion activity was done by the PRC for the residents.

The ICRC is a neutral,

impartial and independent organization with an exclusively

humanitarian mandate that stems from the Geneva Conventions of 1949.

It helps people around the world affected by armed conflict and

other violence, doing everything it can to protect their lives and

dignity and to relieve their suffering, often alongside its Red

Cross and Red Crescent partners.

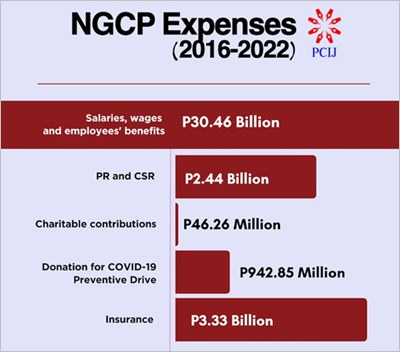

Power grid operator

NGCP billed P2.4B worth of CSR, PR expenses to consumers

Since January 2023, the Energy Regulatory

Commission has held 14 hearings to determine how much the NGCP

should charge customers. The result of the investigation could mean

refunds or higher electricity bills in the coming years.

By

ELYSSA LOPEZ

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

November 7, 2023

MANILA – As the sole public utility

in charge of power transmission lines, the chief mandate of the

National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP) is to ensure the

reliability of the country’s electricity. So when a government

representative found that the company had included corporate social

responsibility (CSR) activities as part of its operating expenses,

she sought an explanation.

“Are CSR expenses necessary for the provision of the transmission

services by NGCP?” asked Marbeth Laconico, corporate secretary of

the National Transmission Corporation (TransCo), during a hearing

called by regulators.

Transco is the state entity that owns the power transmission grid,

which brings power supply from generating plants to electricity

distributors. NGCP, owned by a consortium of Filipino tycoons and

the State Grid Corporation of China, won the concession deal to

operate it after a public bidding in 2007.

Questions over the NGCP’s finances have grown in recent years, as

the transmission operator, a state-sanctioned monopoly, reported

higher profitability. Last year, NGCP reported P34.7 billion in net

income on nearly P62 billion in revenues. Net profit margin grew to

56.15% from 47.6% year-on-year.

Yet based on its financial statements from 2016 to 2022, NGCP passed

on to consumers P2.4 billion in expenses for “public relations and

corporate social responsibility,” P46.2 million in “charitable

donations,” and a donation of P942 million for a “COVID-19

Preventive Drive.”

“NGCP values not only the quality of [its] transmission service. We

also like to put [a] premium [on] engaging with communities, which I

suppose all companies are undertaking as part of their corporate

social responsibility projects,” Raymund Fontillas, financial

controller of NGCP, told regulators.

Regulators have also sought explanations for the huge amount spent

by the grid operator on salaries and benefits paid to employees, as

well as expenses due to force majeure such as natural calamities.

Since January 2023, the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) has held

14 hearings to determine how much the NGCP should charge customers

for the period 2016 to 2022, the fourth round of regulatory reviews.

TransCo and distribution utilities like Meralco grilled the NGCP

during the hearings, where the exchange between TransCo’s Laconico

and NGCP’s Fontillas happened.

Transmission rates are supposed to be set every five years, the

length of a regulatory period. But that has not happened in the past

decade. The last time the NGCP had a regulatory review was in 2010,

which determined the maximum allowable revenue it could earn for

2010 to 2015, the company’s third regulatory period.

The ERC did not call for a formal review of the rates until it

issued the Amended Rules for Setting Transmission Wheeling Rates (RTWR)

in 2022, which officially began the fourth regulatory review.

It does not mean the NGCP has stopped collecting fees from

customers, however. The company has maintained an average net profit

margin of 47.83% from 2016 to 2022. Based on its financial

statements, the company earned an average of P23 billion annually

during the five-year period.

This delay had been the subject of multiple Senate and House

hearings, on top of NGCP’s own delay in the construction of its

interconnection projects that add to consumers' monthly electricity

payments.

At least 9% of what Filipinos pay for electricity goes to

transmission charges. This means that for every P100 spent on the

electricity bill, P9 goes to the NGCP.

How much that 9% costs monthly is determined by the ERC, the

quasi-judicial body in charge of regulating the energy sector.

Insurance bought from shareholder’s firm

The regulatory review hearings provided a venue for the NGCP to

explain the expenses that had been questioned multiple times by

critics.

Among other expenses questioned during the hearings were force

majeure events (FMEs). For the fourth regulatory period, the NGCP is

applying for P1.057 billion worth of FME claims, including related

costs that occurred after 2010 or before the fourth regulatory

period.

Such expenses can be passed on to consumers, subject to the approval

of ERC. Natural disasters such as typhoons, earthquakes, and

landslides, or man-made disasters such as war or riots, are

considered as FMEs.

Under the concession agreement between the NGCP and TransCo, the

former is mandated to insure its assets. NGCP’s financial statements

showed the company spent P2.8 billion in insurance payments from

2018 to 2021, which include industrial all-risk insurance, a type of

policy that allows the policyholder to protect assets from risks

other than fire.

Almost half of insurance policies during the period, or about P1.3

billion, were procured from Prudential Guarantee and Assurance Inc,

one of the country’s largest non-life insurers. Its chairman, Robert

Coyiuto Jr., owns one of the shareholders of NGCP: Calaca High Power

Corp.

Reeva Shane Viado, corporate financial analyst of the Power Sector

Assets and Liabilities Management Corp. (PSALM), the state entity

that restructured the energy sector, sought clarification during the

hearing from NGCP if it had claimed any amount related to FMEs from

its insurance providers.

“It is just our position… that if NGCP has already recovered any

amount from its insurance providers, such amount should not be

included in this revenue under the recovery proposal of NGCP,” Viado

said.

The NGCP representative failed to respond to the question.

The ERC also posed “clarificatory questions” regarding the

compensation package of NGCP employees. In August, the commission

asked NGCP to provide a detailed breakdown and explanation of

salaries, wages, and employee benefits from 2016 to 2020.

Salaries and employee benefits, which totaled P20.9 billion from

2016 to 2020, were the second biggest expense item during the review

period.

Public records showed the NGCP employs about 4,700 employees. That

means each employee earned P4.4 million a year on average, or about

P371,000 a month.

Financial statements also revealed that key management personnel had

enjoyed “short-term benefits” that averaged P346 million from 2016

to 2020. The documents however were silent on what kind of benefits

were paid to these employees.

Fourth regulatory review

With the delay in its regulatory review, the NGCP has been billing

customers based on 2010 rates. A paper by University of the

Philippines economics professor Joel Yu found that the company

“continues to enjoy the rates of return determined by the ERC which

are no longer reflective of the opportunity cost of capital.”

As the rates were determined based on prevailing market conditions

–

just after a financial crisis – a premium was placed on the risk

taken by the NGCP in operating the country’s transmission grid. The

economy has since recovered.

The ERC uses a performance-based review in determining the NGCP’s

wheeling rates. This means the company may obtain cash incentives in

case it performs beyond the target criteria set by the commission.

These criteria are supposed to be reviewed every regulatory period.

Because of delays in the review, the NGCP was allowed to recover an

interim maximum annual revenue from 2016 to 2020 based on criteria

set in 2010. In the ongoing review, the NGCP claimed that customers

owed it P316 billion, or the total revenue requirement from 2016 to

2020.

Based on PCIJ’s analysis of available data, that amount was at least

28% higher than what the NGCP had charged customers during the

review period.

ERC asked the NGCP during the hearings how much the revenue

requirement would translate to per-kilowatt-hour rates, but the grid

operator was unable to reply.

The ERC has decided to catch up on the delay and extend the duration

of the fourth regulatory period, 2016 to 2020, up to 2022, or from

five years to seven years.

The NGCP opposed this, citing the five-year intervals followed in

previous regulatory periods. In October, the ERC denied the plea,

which means the decision on the fourth regulatory review is set to

be published soon.

How the ERC decides on which expenses the NGCP can pass on to

consumers will result in either refunds or higher electricity bills

in the coming years.

Agusan del Norte

residents rebuild lives after armed conflict

|

Yang-yang

Subay says the ICRC’s water project has helped them access

clean water and enjoy better health.

(Photo: M.Lucero/ICRC) |

By

ICRC

October 5, 2023

MAKATI CITY –

Yang-yang Subay remembers the time when conflict broke out in her

village and she had to flee for her life along with her family and

185 other people in March 2022. All they wanted was a place they

could live in without fear of violence. Barangay Puting Bato of

Cabadbaran City, Agusan del Norte province, became that haven for

them.

But the living conditions

were a challenge. Their dilapidated, makeshift homes provided

inadequate protection against heat or rain. A few of the families

were forced to live together in a single house, which they built

using scrap materials salvaged from their former village. They

lacked both space and privacy. Without access to clean water, proper

sanitary facilities or shelter, those were displaced began to have

health problems. “People here began to fall ill because of the dirty

water and many of us had regular stomach aches,” says 23-year-old

Yang-yang, a farmer.

Julie Subay, who was also

displaced, shares that the temporary house he built had only a

tarpaulin roof. “Water used to seep in whenever it rained heavily

and we used to get wet even inside our house,” he says.

A team from the

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) visited Barangay

Puting Bato in March 2023 to assess the condition of the displaced

people.

ICRC

staff check the new water tap stand that was installed in

the village. (Photo: M.Lucero/ICRC) |

The community lives

several kilometres away from their agricultural land and forestry

area and have limited access to basic supplies, timber and water.

This made it hard for them to build sturdy homes. We also discovered

that the residents didn’t have proper toilets because of which they

were even more susceptible to diseases,” says David King, the ICRC’s

water and habitat engineer. Responding to the needs of those

affected by armed conflict on a purely humanitarian basis, the ICRC

built a new water pipeline in the village and provided water filters

for each family. The ICRC team also built another water outlet so

that villagers don’t have to queue up for several hours to collect

water from the only outlet that the village had previously.

To ensure that community

members can repair their homes, install proper roofs and set up

toilets, the ICRC provided them with construction materials. The

Philippine Red Cross also held sessions to raise awareness about the

importance of cleanliness and good hygiene practices.

Melanie Subay, a

28-year-old farmer, says her family’s life has changed for the

better since they received help from the ICRC. The water is no

longer as dirty as it was and the additional water tap is helping

villagers to use their time a little more efficiently. “We used to

wait for many hours to collect drinking water from the single tap in

our area. I used to go to the riverside and wash my clothes. But it

was difficult to carry all the clothes and walk for miles. That is

why all of us are happy that we have another water source near our

homes,” she says.

Julie, her neighbour,

agrees. “My house looks better now and I no longer worry about the

rain. We also don’t feel as hot as before because we have used woven

bamboo mats for the walls and the roof,” he says.

A Woman of Culture,

LOREN LEGARDA

|

Senate

President Pro Tempore Loren Legarda champions Philippine

heritage fabrics in her daily and formal wear. Here, she is

in an abaca silk wrap with piña belt from La Herminia Piña

Weaving Industry of Kalibo, Aklan. |

By

DTI-Bureau of Domestic Trade Promotion

October 4, 2023

MAKATI CITY – The

name Loren Legarda has always been synonymous with the conservation

and promotion of Philippine culture and arts, traditional knowledge,

and indigenous systems.

Senate President Pro

Tempore Loren Legarda’s pursuit to increase the level of cultural

heritage awareness to preserve and protect our age-old knowledge,

traditions, and practices that we inherited from our forefathers can

be seen through all her efforts to champion the cause of cultural

preservation and advancement.

Capacitating culture-based

livelihoods

With a distinguished

career as a journalist and public servant, and a deep-rooted passion

for cultural heritage, Legarda has emerged as a remarkable figure in

Philippine society – a true woman of culture.

This advocacy has led her

to author and sponsor legislative measures and support programs and

initiatives that promote Philippine culture and arts, protect the

rights and traditions of the indigenous peoples, and advocate for

cultural integrity and culture-based livelihood.

“Tayong mga Pilipino ay

sadyang malikhain. Our love for the arts is immeasurable, and this

can be seen in our ancestors’ works. We have to promote it as well

as embrace it. The world needs to know more about the Filipino

culture and artistry – our own identity,” Legarda said.

As a long-time advocate of

cultural heritage and Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs),

Legarda emphasized the need to capacitate MSMEs, including

culture-based livelihoods, as part of the overall strategy on

economic development, providing opportunities for support and

growth, and ensuring that their needs are addressed.

“We need to sustain our

gains by strengthening our MSME programs because aside from

generating employment opportunities and better incomes, MSMEs are

powerful platforms for promotion of viable rural livelihoods,

cultural preservation, socioeconomic empowerment of indigenous

communities, and environmental protection,” Legarda, author and

principal sponsor of the Magna Carta for MSMEs said.

Recently, the Cultural

Mapping Law authored by Legarda was enacted, which sought to make

heritage an inclusive tool for local and national development,

employing a grassroots approach that empowers local communities to

identify and assign cultural value to properties that are important

to them.

Cultural mapping provides

a powerful tool for MSMEs and indigenous communities to infuse

cultural richness into their livelihoods. By preserving and

celebrating their cultural heritage, these enterprises can

differentiate themselves in the global marketplace, create

sustainable livelihoods, and contribute to the preservation of

cultural diversity.

“It is but fitting to help

bring our culture closer to our people, to reawaken the citizens’

pride in our culture, history, and heritage, and to strengthen our

nationalism. We must explore initiatives to reintroduce our culture

and traditions, especially to the newer generation. We must gather

more heritage warriors to conserve and protect the Philippine

cultural heritage effectively,” Legarda said.

Empowering the Philippine

Cultural Capital

Aside from the Magna Carta

for MSMEs and the Cultural Mapping Law, the four-term Senator

initiated several programs and policies to promote our people’s arts

and cultural diversity.

To preserve the art of

Filipino weaving, Legarda pushed for the strengthened implementation

of the Philippine Tropical Fabrics Law, which she principally

authored, as it seeks to expand the tropical fabrics industry and

support the local and indigenous weavers and artisans. She also

coauthored the National Cultural Heritage Act, which primarily

protects the country’s cultural wealth and treasures.

Legarda also filed Senate

Bill No. 1866, or the proposed National Writing System Act, which

aims to promote patriotism among Filipinos by inculcating,

propagating, and conserving the cultural heritage and treasures of

the country through our indigenous and traditional writing systems.

Moreover, Legarda proposed the establishment of a Department of

Culture, which will initiate programs and activities promoting

national identity and culture.

The Senate President Pro

Tempore provided support for the Schools of Living Traditions (SLT)

Assistance to Artisans, Enhanced SLT Program; the establishment of

weaving, natural dye, and processing centers; and the establishment

of pineapple farms and fiber extraction facilities and abaca fiber

production in some localities in the country. She spearheaded

projects covering the protection and promotion of various cultural

traditions, including Hibla ng Lahing Filipino, the Philippines’

first permanent textile gallery; the Baybayin Gallery, the

Philippines’ permanent ancient scripts gallery in the National

Museum; and the Likha-an in Intramuros, a space and repository for

Philippine traditional arts. She also supported and honored the

Manlilikha ng Bayan (National Living Treasures) through the

establishment of cultural centers and a permanent gallery at the

National Museum of the Philippines.

Legarda’s tireless crusade

for the arts does not end in the traditional. She has been the

visionary and driving force behind the Philippines’ return to the

Venice Biennale after a 51-year hiatus, considered as the Olympics

of contemporary art. To further cement the Philippine presence, she

filed a bill that institutionalizes the participation of the

Philippines in the said exhibition. Through her initiative, the

Philippines is also set to be the Guest of Honour for the 2025

Frankfurt Book Fair, the world’s oldest and most prestigious book

fair. To strengthen cultural diplomacy, she initiated the

advancement of Philippine studies in United Kingdom, Germany, Spain,

Singapore, United States of America, South Korea, Australia, Canada,

Mexico, Belgium, Canada, and France.

Just last year, the

Philippine Creative Industries Development Act, which she

coauthored, was enacted, marking yet another milestone in her

relentless efforts to support cultural workers and advance

Philippine culture and arts.

Reignite and Reconnect:

NACF returns after a three-year hiatus

In 2016, to further

showcase Filipino creativity and ensure that the legacy of the

Philippine culture and heritage lives on, Legarda launched the 1st

National Arts and Crafts Fair in collaboration with the Department

of Trade and Industry to create a nurturing environment where our

indigenous crafts and artistry can flourish.

Legarda posed the

question: “The challenge against a fast-changing globalized world is

this: How do we promote, preserve, and sustain the artistic

creativity and culture-based crafts of our artisans deeply rooted in

our respective cultures? How do we support talented weavers, our

culture-bearers, and encourage them to continue their crafts and to

pass on their expertise and art to the next generation?”

The National Arts and

Crafts Fair emerged as a robust platform to address these

challenges. It was designed to support indigenous communities and

local entrepreneurs by providing them with the means to reach

broader local and even international markets. The fair became a

venue that showcased innovative products and celebrated the

indigenous culture and traditions of various Philippine regions.

However, in 2020, the

world grappled with the unprecedented challenges brought about by

the COVID-19 pandemic. The NACF faced an unforeseen hurdle, leading

to a three-year hiatus.

As the world slowly

recovers, the NACF returns with renewed vigor and purpose that drive

Filipino artisans and indigenous communities to continue creating,

innovating, and inspiring.

The return of the NACF

after the three-year hiatus signals a fresh opportunity for us to

showcase the rich and diverse heritage of our country which we must

protect, preserve, and rightfully pas on to the next generation.

“The NACF is back to open

doors of opportunities for our indigenous communities and local

entrepreneurs. Our culture is our soul, and while many do not

realize it, we need to release our cultural energy, which motivates

us to work and engage in meaningful and profound social interaction.

With the return of the NACF, I encourage our artisans to embrace our

diversity and always bring with you the legacies of Filipino

cultural heritage,” Legarda said.

“Undeniably, our MSMEs,

IPs, and culture-based livelihoods have been among the most affected

by the pandemic. To ensure the inclusive and sustainable development

of our cultural communities, we are happy to bring back the NACF. I

invite everyone to visit and participate in this year’s National

Arts and Crafts Fair, not just as spectators but as active

contributors to our cultural revival. Together, let us reconnect

with our roots, rediscover the culture and traditions that reflect

the identity and history of a community, and support the talented

individuals who keep our heritage alive,” she continued.

The Appeal of Bananas

Delicious fruit products

from the Philippines are best-sellers in the EU market

By

Knowledge Management and Information Service

August 24 2023

MAKATI CITY – The

relaxed charm of fourth-generation farmer 35-year-old Raymund Aaron

does not show the hard work he puts into successfully running his

small family business of manufacturing food products.

The company Villa Socorro

Farm and their factory are situated in Pagsanjan, Laguna province,

south-east of Manila.

The self-styled 'Banana

Chief' of this social enterprise, Raymund, oversees the production

and marketing of the company's famous banana chips.

He inherited his passion

for agriculture and farming from his father, incorporating a streak

of his own.

Right after obtaining a

Bachelor of Science in Management from Ateneo de Manila University

in 2009, Raymund joined the budding family business.

"I wanted to be an

entrepreneur for as long as I can remember. We used to grow bananas

on our land in Pagsanjan, and so, after graduating, doing business

using bananas seemed the perfect fit," Raymund shared.

An indirect start

The idea of exporting came

through his father's work in marketing for a multinational company,

which inspired him to engage in international business.

Starting off in 2008 with

an initial capitalization of P5 million, the company produced banana

chips, with the first export in 2014 to the United States.

The Health Safety

Certification from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a

requirement of the Philippine authorities, was obtained in 2012,

which further added credibility to the business as an exporter.

"We began exporting

indirectly through a local company that expressed interest in

distributing our products to buyers there."

Department of Trade and

Industry (DTI) helps reach Europe

Raymund, a regular at the

Philippine government’s DTI business matching events, recently

returned from a similar event held in Dubai coinciding with Gulfood

2023.

Regular participation in

business networking events and seminars since 2015 has provided

valuable knowledge and insights on export market access, including

the European Union (EU).

Be it the DTI or the

Center for International Trade Expositions and Missions (CITEM)

handling the International Food Exhibition (IFEX) Philippines, the

biggest international food trade show in the country, he always

found participation in the trade fairs to be beneficial.

"You never knew who you

would meet. I always carried samples of my products along." At one

such event arranged by the DTI-Export Marketing Bureau (EMB),

Raymund established a connection with the Philippines’ diplomatic

mission in Switzerland. Soon, samples from Villa Socorro reached a

few Swiss companies with the help of this link.

The products were a hit

with one distribution company. By the end of 2019, a 20-foot

container with 1,000 boxes that cost USD14,000 has been shipped to

Switzerland. "It was support from the EMB that helped us pursue

direct exports to Europe. We made our first link through them."

Recognizing the support he

received, Raymund is always willing to share his skills and

knowledge with other entrepreneurs and to contribute to local DTI

capacity-building initiatives.

Why the EU?

The EU appears to be a

lucrative market for the company as Raymund gradually expands the

product range by including sweet potato chips and corn snacks. About

80% of total current revenue comes from exports, while 20% comes

from sales at hotels, restaurants, canteens, airports, kiosks, and

selected supermarkets in the Philippines.

Villa Socorro's exports to

Europe are at 5%, with buyers in Switzerland, Norway and EU member

state the Netherlands. Raymund wants to increase business with

Europe, specifically with EU member states, which he regards as the

best destinations for healthy organic food products made from

tropical fruits.

"It is a market that is

willing to pay a premium for natural products."

EU buyers' requirements

Raymund's drive to grow

specifically in the EU market is evident in his readiness to comply

with the necessary requirements.

The REX number to avail of

the EU Generalized Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP+) scheme to

export tariff-free to the EU was obtained on the recommendation of

the buyers to strengthen the business.

The Registered Exporter

System (REX) is a self-certification system wherein the origin of

goods is declared by economic operators themselves by means of

so-called statements about origin. To be entitled to make out a

statement of origin, an economic operator must be registered in a

database by the competent authorities. The economic operator then

becomes a "registered exporter."

Product and packaging

development were also adjusted. There is a shift to use a more

natural Brown Muscovado Sugar to suit customer preferences in the EU.

The company also created a

sub-brand, Farmony, to market its products in the EU. "Farmony

creates harmony between farmers, manufacturers, and consumers. Our

existing brand, Villa Socorro Farm Sabanana Banana Chips, really

targets Filipinos or people looking for Filipino products. We

created Farmony to have a product that can easily blend on the

shelves of the EU market," Raymund shared.

Social entrepreneur

Being on a farm allowed

Raymund to become a social entrepreneur. He understands well the

needs of the farmer.

To support banana farmers

around his family plantation, Raymund buys 98% of the fruit from the

community that he fondly refers to as “partner-farmers."

"We buy bananas from more

than 200 farmers in a radius of 5km around our farm. We only plant

2% of the bananas that we use for banana chips," he shared. By

processing 600,000 tons of bananas every year, he provides the local

farmers with a market for their produce.

He considers himself lucky

that things fell into place, enabling him to give back to the

community that helped him get to where he is today.

Gearing up for the future

"I am still here. I look

forward to expanding our business. Sticking with the snacks theme,

we're looking at making use of the abundant farm produce in our

region and the rest of the Philippines to create fun and healthy

snacks.

Raymund is determined to

transform the business into a reliable food company by creating an

entire line of banana products and drawing in loyal customers at

home and abroad.

The ARISE Plus Philippines

project is enabling Philippine exporters to take advantage of

European Union (EU) market access and the trade privileges granted

under the Generalized System of Preference (GSP+). It supports the

overall EU-Philippines trade relationship and trade-related

policies.

ARISE Plus Philippines is

a project of the Government of the Philippines, with the Department

of Trade and Industry as lead partner together with the Department

of Agriculture, Food and Drug Administration, Bureau of Customs, the

Department of Science and Technology, as well as the private sector.

It is funded by the EU with the International Trade Centre (ITC) as

the technical agency for the project.

Nature’s Legacy home

décor: Dare to innovate

Eco-friendly home décor

makes space in Europe

By

Knowledge Management

and Information Service

August 14, 2023

Respect for nature and humans

The founders of Nature’s

Legacy, husband-wife team Cathy and Pete Delantar, came from humble

beginnings with no plans to start a manufacturing business.

Witnessing the poverty in

their surrounding community, they made a commitment to help by

creating employment opportunities.

“Our Filipino upbringing

instilled in us a thrifty attitude towards the resources we were

given. We would use woven baskets or buyots when going to the public

market,” recalled Pete.

Cathy and Pete transformed

natural resources into patented sustainable materials to create

inspired pieces for the home, for business, and for life.

In turn, the couple

accommodated unskilled craftsmen, taught them the basics of material

application, and turned them into productive individuals.

Ditching dead wood

Nature's Legacy faced a

challenging journey as a sustainable manufacturer.

Its flagship product,

Stonecast – a handmade material that mimics real limestone – was

quickly imitated by other players in the industry.

“Realizing that we could

not compete on price, the company decided to focus on creating

something unique and different,” Pete shared.

During a walk on their

property in Compostela, Cebu, the founders stumbled upon piles of

forest debris that were being used solely as firewood.

With a background in

material application, they soon transformed the readily available

but ignored raw materials into the sustainable invention Naturescast.

Their current range of

products includes Naturescast, Nucast, Marmorcast, and Stonecast.

All four products align with the manufacturing company’s sustainable

product principles: recycled, biodegradable, ethical, and communal.

Destination: export

In 1983, Nature’s Legacy

began exporting to Canada and the United States. At that time, the

company's revenues ranged between P5.0 to P6.0 million per year and

the foreign exchange rate was P18 - P20 to the US dollar.

In 2002, the company made

its first exports to Germany. Today, almost 40% of Nature’s Legacy’s

total exports go to Switzerland and EU member states including the

Netherlands, France, Italy, and Slovenia.

GSP+ does the trick

One of the company’s

objectives is to attract customers who prioritize sustainability,

and who recognize the value and significance of sustainable,

circular, and innovative products and practices. This is the reason

the company has zeroed in on the EU as its niche market.

The EU’s Generalized

System of Preference Plus (GSP+) scheme for Philippine exporters has

created an attractive incentive for firms to do business with EU

member states since 2017, according to Pete, who learned about the

scheme through the Philippine Exporters Confederation, Inc. (PHILEXPORT)

and the Philippine government’s Department of Trade and Industry

(DTI).

“We learned that it

provides advantages not only to our company but also to other

Philippine exporters who sell products to the EU. The elimination of

tariffs on over 1,000 Philippine products under GSP+ can enhance

exports and increase competitiveness.”

Sustainable partnership

with the government

Pete expressed their

appreciation for the continued support from the DTI.

The company received

training, seminars, participation in trade shows, support in product

development, and business matching and networking.

“The agency allowed us to

know customers better – their European culture and design

preferences. By knowing the market, we can tailor-fit our products

and innovation to match their needs,” Pete shared.

DTI’s publications were

instrumental in Nature’s Legacy products getting noticed by the

buying public. Pete and Cathy’s engagement in various missions and

programs added to the buyer’s familiarity with the products.

Walking the talk

Pete and Cathy have not

forgotten their original resolve to support their community through

their business.

Some of the 89 current

employees of the company are second-generation workers who are

equipped with higher education.

“We make sure to take care

of our employees’ basic needs like food, clothing, and shelter. We

also provide them with subsidized housing and quarterly bonuses,”

shared Cathy, who, together with her husband, believes in the

Sustainable Development Goals in uplifting the lives of their

workers.

Their employees live a

mere 15-minute walk from their factory in Cebu and are therefore

contributing to reducing the carbon footprint of their operations.

Looking upwards with ARISE

Plus

Upon the recommendation

from PHILEXPORT, the company was engaged in the ARISE Plus

Philippines project, an endeavor designed to support small- and

medium-sized businesses in the country and open new doors of

opportunity.

“Our aspiration is that,

with the support of ARISE Plus, we can expand our reach to more

buyers and customers who prioritize and share the same values of

Sustainability, Circularity, and Innovation,” said Cathy.

This is also in line with

Pete and Cathy’s future goals for Nature’s Legacy.

Pete and Cathy, tenacious

experts who never give up, plan to introduce into the market a

compact yet revolutionary shelter for people facing disasters or in

need of temporary lodging during a transitional period.

The envisioned shelter is

a breeze to assemble, making it an ideal solution for women and

elderly members of the community looking to contribute to building a

resilient dwelling during trying times.

Nothing is holding back

the couple in daring to undertake innovative solutions, making smart

choices with the use of ingenious materials to produce a

quick-to-install shelter.

The ARISE Plus Philippines

project is enabling Philippine exporters to take advantage of

European Union (EU) market access and the trade privileges granted

under the Generalized System of Preference (GSP+). It supports the

overall EU-Philippines trade relationship and trade-related

policies.

ARISE Plus Philippines is

a project of the Government of the Philippines, with the Department

of Trade and Industry as lead partner together with the Department

of Agriculture, Food and Drug Administration, Bureau of Customs, the

Department of Science and Technology, as well as the private sector.

It is funded by the EU with the International Trade Centre (ITC) as

the technical agency for the project.

A bagful of success

Trendy PH handbags impress

fashionistas in Europe

By

Knowledge Management and Information Service

August 10, 2023

MAKATI CITY –

Jennifer Lo is a living proof that an eye for aesthetics can be

inherited. Based in Makati City, Metro Manila, the third-generation

entrepreneur has carried on her family’s business of handicrafts –

the Larone Crafts, registered in 1984.

Growing up, she helped her

mother during trade shows, observing how business was conducted with

foreign buyers and taking minutes of business meetings.

After completing a short

course on Manufacturing Management at the Fashion Institute of

Design and Merchandising in Los Angeles, United States of America

(USA) in 2006, she worked with various fashion companies before

coming back to the Philippines to help in her mother’s handbag

business.

“I’m the steward of my

parents’ and grandparents’ hard work. My goal is to make the

business sustainable for another 20 years,” shared Jennifer.

Operating out of a compact

500-square-meter office that includes a production area and

warehouse on the top floor, she exudes a hands-on demeanor.

Tradition à la mode: When

tradition meets fashion

Larone Crafts’ designs are

modern but remain true to Pinoy traditions by incorporating Tinalak

weaves and the woven fabric Inabel. Natural plant fibers such as

abaca, raffia, and seagrass sourced from all around the Philippines

add an indigenous charm to her products.

The results are timeless

accessories that buyers can keep in their wardrobes season after

season.

“The bags are meant to be

used all year round. We do not make items that are just for a

certain season to be thrown away the next. We manufacture them to

last.”

In the collection of

Larone Crafts’ handbags, the signature hand-embroidered clutch bags

are a particular hit with buyers.

Carrying on the export

mission

The agility of Larone

Crafts in staying abreast with technological advancements and design

trends has kept it exporting successfully over the years.

The company’s first

exports were made in 1984 to the USA. Back then, Jennifer was only

three years old.

“I can see how conducting

international business at a time when the Internet was not yet

existing must have been quite a challenge,” said Jennifer,

expressing her appreciation for the ease and speed that

technological advancement has brought about over the years.

In 2009, when Jennifer

joined the company, she continued to step up to evolving market

trends.

“Smaller niche brands were

coming into the field. Rather than large containers of orders with

thousands of pieces of the same style, orders of several styles and

colors in a few hundred pieces were preferred.”

In 2022, following the

pandemic, 3% of Larone’s customers were from the European Union (EU),

90% from the USA, and the rest a mix from other countries.

Going international with

help from the government

For a long time, the only

way to start an international business was through participation in

trade fairs, which is not an easy thing to do alone.

The company has been part

of the Manila FAME almost every year since the 1980s. Showing at

Maison et Objet, NY Now, and Ambiente over the last 10 years has

also been fruitful.

“We received support from

the Center for International Trade Expositions and Missions (CITEM),

the export promotion arm of the Philippine government’s Department

of Trade and Industry (DTI), to participate in international trade

shows in the EU and in the USA. Before the internet and emails, this

was the only way of gaining new overseas customers.”

Jennifer feels that her

company’s participation in these trade shows has been instrumental

in reaching customers, particularly in the EU. Trade shows boost

market research, linkages, design aesthetics, and competitiveness.

She emphasized that

CITEM’s support in terms of product design, booth design and

implementation, and pre-show marketing has been invaluable in

upgrading her business.

“These are all high costs

that would be difficult for our small business to absorb when

initially trying to enter into a new market.”

GSP+ for the EU

Jennifer sees many

benefits from the EU Generalized System of Preference Plus (GSP+).

“The EU GSP + makes our

products more competitive in the EU market by reducing the cost of

importing our goods into the country for our buyers. It improves

access to the 27 countries in the EU.”

Larone Crafts is already

exporting to Spain and the Netherlands, with samples sent recently

to Italy which are expected to generate more orders.

“The EU is an attractive

export market for our company because of the ease of doing business

with their bilingual teams, the market’s love for sustainable,

handmade, and natural products, and the favorable trade policies

such as the GSP+.”

Leaving no one behind

As Jennifer works towards

expanding her product assortment in home and lifestyle products, she

is cognizant of those who work for her.

Depending upon the volume

of orders, in any given season, she employs approximately 100

workers.

She not only retained

artisan families from her mother’s time, but also sources from small

businesses that employ women.

“We work with weavers and

artisans in their communities from all over the Philippines, giving

them a reliable livelihood and helping to preserve the region’s

traditional crafts.”

The ARISE Plus Philippines

project is enabling Philippine exporters to take advantage of

European Union (EU) market access and the trade privileges granted

under the Generalized System of Preference (GSP+). It supports the

overall EU-Philippines trade relationship and trade-related

policies.

ARISE Plus Philippines is

a project of the Government of the Philippines, with the Department

of Trade and Industry as lead partner together with the Department

of Agriculture, Food and Drug Administration, Bureau of Customs, the

Department of Science and Technology, as well as the private sector.

It is funded by the EU, with the International Trade Centre (ITC) as

the technical agency for the project.

Moneyed kin, personal coffers paved Senate victories in 2022

Senatorial candidates in the 2022 polls won

fresh terms by financing their campaign with money from family

members and money from their own pocket.

By

CHERRY SALAZAR

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

May 10, 2023

Loren Legarda won big time

in her comeback bid in the Senate last year, coming in second with

24.3 million votes. She got a lot of help from her son and father,

whose combined contribution to her campaign kitty totaled P136

million, based on her own declarations.

Sherwin Gatchalian

reported receiving a hefty P89 million from three family members,

while Juan Miguel “Migz’’ Zubiri and Joseph Victor “JV’’ Ejercito

each accepted at least P20 million from their parents to secure

fresh terms in the Senate during the 19th Congress.

Zubiri was eventually

elected Senate president.

It is expensive to run for

office in the Philippines. The 12 winning senators reported a total

campaign spending of P1.5 billion in their SOCEs, an amount that

watchdogs said may be an underreporting. Three candidates ran ads on

mainstream media that were worth more than P1 billion, based on

published rate cards or before discounts were given to the

candidates.

Billionaire donors and

business executives have always played key albeit covert roles in

the campaign of national candidates.

But the 2022 senatorial

race showed that some candidates relied more on the money of family

members as well as their own to fund their campaign.

Election lawyers said

receiving financial support from relatives could lead to a possible

conflict of interest especially if the family members also have

business interests.

“[T]here is a tendency for

campaign contributors to be able to dictate or influence the

candidates should they win the election. So when you have a business

interest… then this particular influence is magnified,” said lawyer

Izah Katrina Reyes, policy consultant of poll watchdog Legal Network

for Truthful Elections (Lente).

The “quid pro quo

agreement” for a business to benefit from the influence of an

incumbent official can be “really a possibility,” Reyes said.

Election lawyer Donnah

Guia Lerona-Camitan said it also “raises questions whether elected

officials can make impartial decisions against the interests of

their family businesses for the benefit of the public’s interest.”

Six of the 12 winning

senators received a total of P291.91 million from their own

families, according to the statements of contributions and

expenditures (SOCEs) that the candidates submitted to the Commission

on Elections (Comelec).

Family and personal funds

accounted for a fifth of the P2.18 billion total spending reported

by 48 candidates in their SOCEs. Sixteen candidates did not submit a

finance campaign report to the Comelec.

Two neophyte senators –

Mark Villar and Rafael “Raffy” Tulfo – funded their campaign from

their own pocket. Their combined campaign bill ran up to P170.61

million, based on their SOCEs.

A “limited or confined

support base,” such as electoral campaigns largely funded by

relatives or personal money, is not ideal, Reyes told Philippine

Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) in an interview.

“What we really want is a

more distributed support base for our candidates in terms of seeing

their campaign contributions… We want more active participation from

our voters and the public,” she said.

Top donors backed Legarda

Two of the top five donors

backed the campaign of Legarda, who came in second behind actor

Robinhood “Robin’’ Padilla.

Her son Leandro Leviste

gave her P100 million, while her father Antonio C. Legarda shelled

out P36 million. These account for 86 percent of the senator’s

declared contributions.

Leviste is the founder and

president of solar energy firm Solar Philippines.

According to an earlier

PCIJ report, Leviste’s Solar Philippines cornered a significant

share of the government’s Green Energy Auction Program (GEAP), a

Department of Energy program that allows renewable energy developers

to bid for supply contracts at a set ceiling price.

During the first auction

in 2022, the firm won 90.58 percent of auctioned solar capacity, or

1,350 of 1,490.38 megawatts (MW), and 70.16 percent, or 1,380 of

1,966.93 MW, of renewable energy capacity across all technologies.

Solar Para sa Bayan Corp.,

a subsidiary of Solar Philippines, also received a 25-year

distribution franchise from Congress which then President Rodrigo

Duterte signed into law in 2019. At the time, Legarda held the lone

congressional seat for Antique province.

Some lawmakers, renewable

energy groups, and energy advocates opposed the legislative

franchise, as it “effectively grants a monopoly and exempts one

private company from the rules of competition and oversight.”

|

Solar

Philippines founder and president Leandro Leviste welcomes then

President Rodrigo Duterte and his mother, Sen. Loren Legarda, at

the firm’s factory in Sto. Tomas, Batangas. Solar Philippines

would be granted a 25-year franchise in 2019.

(Photo from the Facebook page of the Presidential Communications Office, August

2017) |

Former Comelec

Commissioner Luie Guia said a donor’s relationship with a candidate,

“whether there is a violation or not, is already a red flag for a

potential conflict of interest.” But he added that it is more

important that disclosures are honest.

Legarda said she did not

defend the bill on the floor and abstained from voting “out of

delicadeza” because the firm is owned by her son. “In fact, I would

always be out to make sure that there is no conflict,” she said in

2019.

Reyes said Legarda’s

abstention was “a good start to maintain neutrality…but what we

don’t see are the discussions maybe among colleagues.”

Currently, eight bills on

solar and renewable energy are pending at the committee level in the

Senate. None of the bills were authored by Legarda, but she has

publicly supported green initiatives in the past.

Gatchalian and family

firms

Family and business

partners helped Gatchalian secure his reelection. He ranked fourth

in the race with 20.6 million votes.

More than half of the

contributions he received, or P81.91 million, were from his kin:

over P58.41 million from his mother Dee Hua; P15.5 million from his

brother Kenneth; and P8 million from his maternal aunt Elvira Ting.

Dee Hua is the second top

individual donor, next to Leviste.

The Gatchalians have

interests in various industries from plastic manufacturing to hotels

and casinos, banking, and mining.

Earlier this year,

Kenneth, director of Altai Philippines Mining Corp., was embroiled

in a controversy over alleged illegal mining operations in

biodiverse-rich Sibuyan Island in Romblon. Protesting residents

accused the company of operating without necessary permits and

violating environmental policies.

The senator himself owns

9.71% shares in Wellex Industries, Inc., a mining and oil

exploration firm, according to the company’s reports to the

Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) as of April 2023.

In separate bills,

Gatchalian proposed amendments to the Oil Exploration and

Development Act and the Philippine National Oil Company charter. He

also proposed income tax incentives for petroleum service

contractors. These bills were referred to the committee on energy,

where he sits as vice chair.

Bills on the suspension of